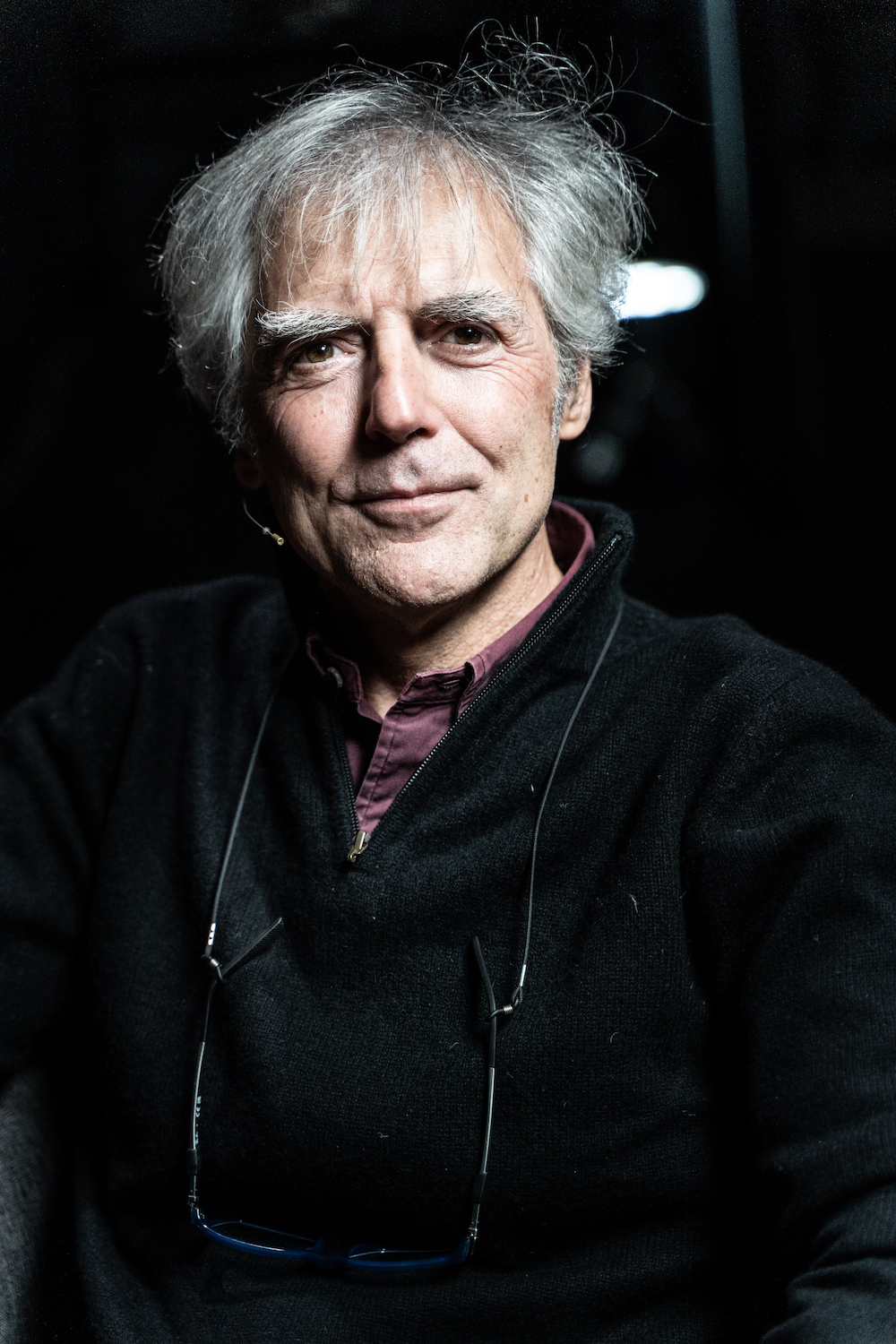

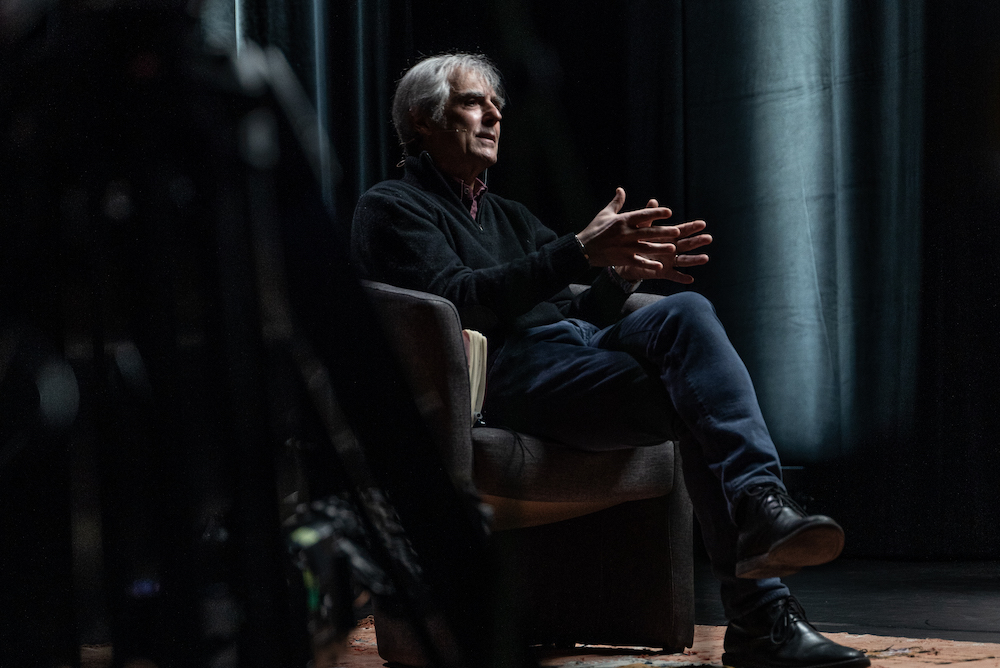

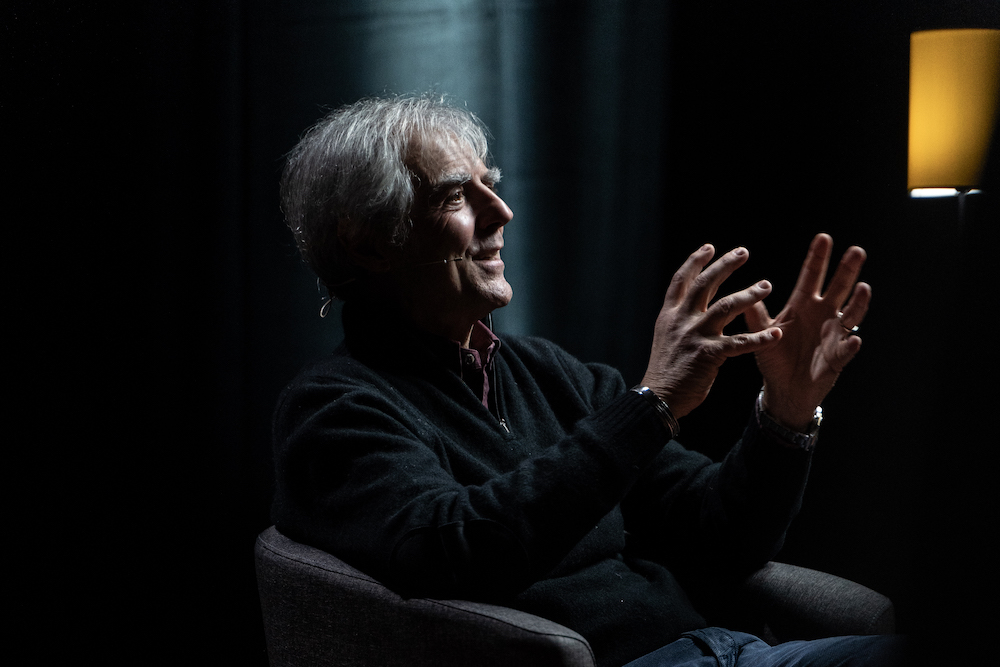

Roberto Beneduce, Ethnopsychiatrist and Anthropologist (Italy) who took part in the conference 02: Stories for Healing?

en français

[Podcast in French]

Roberto Beneduce, psychiatrist and anthropologist, is a professor of medical anthropology at the Department of Cultures, Politics and Societies (University of Turin) & Director of the Frantz Fanon Centre, which he founded in 1996 with the aim of building a critical ethno-psychiatry.

His clinical work and ethnographic research concern the condition of immigrants and refugees, as well as the treatment of torture victims, the anthropology of social and political violence in sub-Saharan Africa (Cameroon, Mali, Democratic Republic of the Congo), changes in local therapeutic knowledge (churches of healing).

— an interview conducted by Vassili Silovic, author and director of documentary films, recorded at Les Champs Libres (Rennes) in December 2023 in the framework of the serie “What stories for our time?”.

Roberto Beneduce

« Fight with stories indifference »

I could start by saying that in their stories, asylum seekers’ stories entitled to international protection, there’s a real fight for the truth. They have to fight to be recognised as sincere individuals who tell the truth, who aren’t making things up.

Question the story.

When dealing with migrants or asylum seekers, we recognise our ignorance. We know almost nothing about their journeys, be they human, political or religious. As operators, social workers, or clinical workers, we know odd details about their country of origin, maybe a few words of their language, but we know nothing of their personal history. So, to suspect they’re not telling the truth above all, reflects our epistemic anxiety.

Believe the story.

This happens in greater detail when collecting their stories, their memories. It all proceeds in this opaqueness. There’s always been suspicion towards marginalised sectors of any society. Those at the bottom of the ladder, the inferior, are not believed. The situation is a reminder of the colonies. The colonised might say things but not necessarily the truth. Referring to colonial-era anthropology, it’s often noted that it’s difficult to create a relationship of trust and a direct, sincere exchange with informants. The more a nation-state fabricates its systems of realities and truths, recognition of an individual with its own bureaucratic definitions, the more things will escape us.

The opacity of the narrative.

Suspicion is at the heart of bureaucracy. One could say that as each bureaucracy progresses, the more it creates zones of suspicion and inadequacies. I remind my colleagues of Abedemalek Sayyad’s words when he said we must aim for the opacity of authentic discourse. True discourse is always somewhat opaque.

When we try to understand and see everything clearly, we’re probably already mistaken.

Confront the coherence of the story.

Migrants arriving in Europe are well aware they’ll be exposed to a test of truth. They know this harsh examination process and are prepared to confront a system which will subject them to an examination of truth. They are pushed to tell the truth, but according to our criteria of truth and credibility.

The story must be coherent, must provide a logical chain of reasons for leaving their country, and prove their traumatic experiences. Ultimately, their escape must follow a linear progression that, as one can imagine, doesn’t exist in real lives of real people. The decision to leave one’s country is very complex. If we consider just the awareness of risking one’s life, we can well imagine how, in making these choices with everything preceding these choices, there are so many variables that imagining they can be laid out in a coherent line is naive.

We must admit that our coherence is an act of violence. Even in the Istanbul protocols which are designed for torture victims, there is a phrase stating there is a risk of embellishment, making their stories more interesting.

The imposed narrative of a constrained truth.

I always tell my interlocutors, can we define the stories of those seeking, come what may, a place to live or to survive, as lies, when our governments, our politicians, our economic choices are full of lies? Lies and hypocrisy fill our discourses in the name of “national interest” green-lighting anything they like in other countries where sovereignty is suddenly eradicated. Compared with those lies their small lies bear no weight.

The real storytellers are the governors, not the asylum seekers. So, we really need to differentiate the weight of their lies from our lies. We’ve created a nonsensical division between economic migrants and political migrants.

For us, poverty isn’t the same thing as violence.It’s the hypocrisy of our capitalist and neoliberal system, which won’t recognise that the economy is the breeding ground of everyday violence. And that poverty is the primary source of violence and suffering. To flee this violence is a right.

And the fact of separating both profiles has led many to use the profiles of political migrants fleeing violence and war, even when wanting to escape another violence just as intolerable: the violence of poverty. Violence denies the right to food, to medical treatment if you are sick to go to school. As long as we maintain this ridiculous division, there’ll always be someone who has the right to lie to meet our criteria.

I think that in almost every case, our stories are true from the moment we see or recognise true suffering. It’s difficult to lie about one’s suffering. People who collapse, those haunted by images of the dead, or those who have disappeared, these are true stories.

The trivialization of the narrative, by its context.

I’ve heard hundreds and hundreds of these stories. I’ve been confronted so many times with people who say: “I’ve been bewitched.” “I’m being manipulated by someone, I’m a victim of a spell.” These trivialised stories, considered naive, stories of gullible people, have to be reconfigured on the basis of their cultural complexity. And set up a sort of struggle package, meaning that those being threatened, fighting, evil, hostility, jealousy are not just crazy, they’re not just victims.

This transformation of their hardship into epic tales can only work on the condition we recognise the entire history of these misunderstandings and the trivialisation of their experience. To authenticate an experience we need an epistemic, clinical, and political effort.

Scriptwriters have to imagine that every experience has value provided it’s heard and recognised as a result of a person’s experience. For complex experiences to become epic means first of all recognising the historical truth, recognising the truth of the experience, which is not necessarily the reality of the experience.

The epic dimension of the story.

An epic story means giving the person the possibility of feeling, in some way, a bit of a hero in their hardship. We must understand that the epic dimension carries elements of contrast and struggle. These people are not given the right to be aggressive, they have to be victims.

Therefore the epic dimension is also a way to offset, to oppose the victimisation aspect which dominates our discourse. We accept you if you are traumatised, we accept you if we can domesticate you. The epic dimension, it’s risky, also allows for an empowering discourse, an aggressive discourse. This is the most substantial part in clinical work. Even for a scriptwriter. The characters shouldn’t be coherent, good, or faithful. They must also reveal the darker areas of our societies, of our relationships, and families.

The story, its mutation, its archiving.

This is where the epic dimension explodes. It overturns the trivialisation that even our clinical and legal categories risk reproducing perpetually. We’ve become an odd form of archives, archives that weren’t prepared, with an accumulation, a mass of tragedies, dirty businesses, imperfect, incoherent stories, etc. This means that today’s clinical records may, in a couple of centuries to come, be unique archives of today’s crisis, which is the crisis challenging the notion of borders, the state and nationality. Today’s narrative, for it to work in order to be therapeutic, has to be a counter-narrative.

Meaning, not just settle for labels: “credible asylum seeker,” “traumatized asylum seeker.” But rather say: an asylum seeker coming from a country experiencing violence due to international lobbying, due to my own government’s interest, etc.” You see, we need to reclassify our categories, rethink the way we welcome asylum seekers, immigrants in general.

The responsibility of screenwriters.

A word of advice to all scriptwriters aiming to create narratives based on your experience? You know already that scriptwriters today cannot escape this huge responsibility of sharing together with other experts, with others, on today’s violence. And your characters, your stories, are a means to fight against the worst of all evils: indifference.

© Photos Brigitte Bouillot

Podcast: Play in new window | Download